This blog is based on a talk I gave at The ResusNL conference in The Netherlands and you can see a recording of it here. It was my first speaking opportunity outside of the UK and I was incredibly nervous but everyone was very welcoming and made me feel at ease. I hope you enjoy it too.

Let me present you with a case…

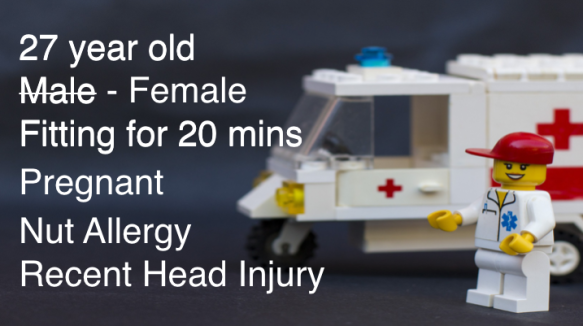

You get an alert call from the ambulance service: they are bringing in a patient. He is 27 years old, collapsed at a restaurant and has been fitting for the past 20 minutes. The paramedic team say they will be at the hospital in five minutes.

What do you think might be wrong? What is your diagnosis?

Five minutes later the paramedic crew arrive. The patient is still fitting BUT as the team transfer them on to the resus trolley it becomes obvious that there has been a mistake, this is not a man, it is a woman… AND she is in the later stages of pregnancy!

Has this changed what you think might be wrong? Has your diagnosis, or diagnoses altered?

Five minutes after that her husband arrives. He is less distressed than you might expect, given the state of his wife and unborn child, and he provides you with some further history. She has an allergy to nuts but hasn’t ever needed to use her Epipen. She has also felt a bit tired recently, with a bit of a headache, but put it down to the bump on her head she got about a week ago when she slipped and fell in the bath.

What are you thinking now?

Whilst this story is certainly a little contrived, it demonstrates something that those of us in Emergency and Critical Care are well aware of… in the resuscitation setting, any information that you receive will be limited, is likely to change and may well turn out to be wrong altogether! It is actually amazing that, in the face of such problems, we manage to come up with a diagnosis at all, let alone a management plan… and yet… that is exactly what we do, what each of you were doing as you read that case history. As you took in each piece of information you were already thinking of a likely diagnosis and considering treatment options. Not only that, as the information changed you barely missed a step, reconsidering your current diagnosis, deciding whether this would change your strategy or not and if necessary creating a new plan in an instant. From the limited, changeable information I provided, you managed to create a coherent resuscitation plan in a matter of seconds. Have you ever stopped to consider how IMPROBABLE this is? Have you ever wonder how it is that you are capable of making this type of decision, ever wondered how it is that you can take this limited amount of data and turn it in to a useful working diagnosis?

Firstly let’s start with what you are NOT doing!

The standard way we were taught to make a diagnosis is to gather information through a detailed history, carry out a thorough examination, decide upon investigations and with this information go on to create a list of possible differential diagnoses.From here we ask further questions, carry out further tests and eventually settle on what we believe is the most likely diagnosis. We are gathering all the relevant information, considering it carefully and then weighing it up objectively to come to our diagnosis. It is essentially an ANALYTICAL process.

Now, it may be tempting to believe that we behave in the same way in the resuscitation room, it’s just that we do it more quickly. However, that simply isn’t true and if we stop to think about it the reasons become obvious.

ANALYTICAL thinking is heavily reliant upon having accurate access to significant, often very specific, pieces of information. It also takes a lot of processing time so that in a dynamic setting, when we finally do get an answer, it can often be out of date. You see, the more uncertainty there is about data, the more variables there are and the more fluid the situation is, the harder it is to get an answer using an ANALYTICAL process.

Incomplete information. Multiple variables. Dynamic data. Isn’t that exactly what a Resuscitation consists of? Analytical thinking just won’t function well in these circumstances.

So, if that is what we are NOT doing what is our alternative? What type of thinking ARE we using during a resuscitation… because clearly we are doing something that works!

Let’s try an experiment that I hope will help explain, using a piece of pipe and a simple question…

What volume of fluid do you think this pipe can hold? Go on, have a think.

Now, you could try and solve this ANALYTICALLY using the formula for the volume of a cylinder: πr2l This will give you the exact answer BUT it depends on you gathering two vital pieces of information… the radius of the pipe and its length. Without these you are stuck… and you don’t have them!

This problem then forces you in to a different approach, a different way of thinking. Rather than using an analytical formula you can use your experience: your experience of looking at the shapes and sizes of objects. This pipe is clearly bigger than a 50ml syringe but it’s smaller than a 2 litre carton of milk. It is clearly longer than a standard can of fizzy drink but is certainly narrower. If the pipe was a glass can you imagine pouring a can of cola in to it? Would it take the whole can or not… probably not but it would be close. Given a can of fizzy pop is 330mls this pipe probably holds about… I wonder how much you decided???

This process of using previous experience to draw upon similar situations, adjusting them depending upon perceived similarities and differences and then giving a ‘best guess’ answer is called ANALOGICAL thinking.

It turns out that this way of thinking is actual what our brains are best set up to do. Day to day, we naturally draw on an incredibly broad spectrum of our past experiences to try and make sense of our present situation. We do it sub consciously when we make decisions about the food to choose from the buffet at lunchtime, the quickest way to walk down the street on our way to our hotel or who we choose to sit beside, or not to sit beside, in the conference hall, our present understanding of these situations is shaped by our past similar experiences.

It turns out we are probably doing the same thing when we are in the resus room. We are using our experience of previous similar patients, similar presentations, similar patterns of observations and then use them to create a composite ‘best guess’ of what we believe is happening. Not only that, as the situation develops – as more information becomes available or if it changes – we are constantly updating our view, adjusting it according to how it fits, or doesn’t fit, with our current model of the patient.

It is an incredibly powerful and flexible way of thinking, it is the thinking of experience, the thinking of experts, and is ideally suited to our work in resuscitation.

I think it is really important that we understand and embrace what we are doing because it is only then that we can start working on improving our practice. We have a responsibility to our patients to consider how we can become better analogical thinkers and I’m going to offer three suggestions as to how we can do this.

They are: Feedback. Recording our Thinking. Deliberate Practice.

Feedback is vital to the analogical process. We must have accurate feedback on our diagnoses. Analogical thinking relies upon us having a large database of experience to draw upon, and knowing the outcome last time we faced a similar situation is essential for making this experience useful. Unfortunately for us, immediate feedback on our diagnostic decisions is often limited. Patients move on with a presumptive diagnosis, and the final answer may still be days or even weeks away. We need to ensure a system is in place to get the definitive diagnosis back to us so we can compare it with our initial thoughts. Without this feedback our experience is, essentially, meaningless. Feedback MUST happen.

This brings us to action number two, Recording our Thinking. We need to record our thinking in our medical notes, not just our diagnosis. Due to the delay in obtaining definitive feedback, linking it to our thoughts at the time in a meaningful way can be difficult. How can I understand whether my thinking was correct or incorrect during a particular experience if I cannot clearly remember my thought processes at the time? How will this help? Let me explain with an example from my school days!

From as far back as I can remember my teachers used to tell me to stop just writing down the answers to maths questions. Instead I was told to write down clearly the steps I had taken to get my answer. Why did they ask me to do that? Well, this had three significant advantages.

Firstly, if I got the answer wrong, the teacher could see what I was trying to achieve and could still give me some credit for what I had got right. Secondly, when correcting the question, both the teacher and I could see and understand where I had gone wrong and work on fixing whatever that problem was… a lack of knowledge perhaps; a simple calculation error; or maybe the application of a correct formula but in the wrong circumstances. Understanding why I had got the question wrong was actually more important for learning than knowing whether I was right or wrong. Thirdly, the act of writing the calculations down helped improve my work by reducing simple mistakes or assumptions, as it forced me to actually process and consider what I was writing. Writing my thoughts out actually helped me get more questions right!

These three benefits, understanding, educating and improving, are something we as clinicians can also take advantage of. We know that we are going to make mistakes so having a record of our thought processes helps those judging us in retrospect to understand our thinking and to appreciate the difficulties we faced at the time. This should, hopefully, result in a fairer and more useful outcome when complaints or errors are investigated… something beyond just blaming someone for getting the answer wrong!

Regardless of the outcome, it creates an opportunity to educate. Writing down a summary of our reasoning gives us a better chance to review our own decision making… or that of a junior colleague… when revisiting a case. Rather than concentrating on WHAT diagnosis we settled on, we can dig a little deeper in to our clinical thinking and spend time considering WHY we got to a diagnosis, regardless of it being right or wrong, and gain insights in to HOW we think.

Finally writing our thinking down seems to help us to see errors or false steps in our diagnostic decision making. The only intervention shown to improve diagnostic accuracy is the act of having to restructure one’s thoughts. Taking the time to write down WHY you think a diagnosis is correct actually appears more likely to make that diagnosis correct.

Making the effort to write down what we are thinking helps later understanding of a case by others, helps our own education as diagnostic thinkers and helps improve our diagnostic accuracy.

Finally we come to action number three: Deliberate Practice. Any skill can be improved by deliberate practice and analogical diagnostic reasoning is no different. So, how can we practice?

Firstly we have hundreds of patients coming through our Emergency Departments every day and we can apply our analogical skills to any of them that we choose. We have the opportunity to compare our initial thoughts on any patient, based on their triage information, the EMS handover or the initial presentation of a junior colleague, with the eventual, more thorough, more ‘analytical’ outcome! We can do this with our trainees too, encouraging them to make and explain early diagnostic decisions before doing a more thorough work up of the patient.

Secondly, we can share experiences with each other by discussing cases with colleagues. This doesn’t just broaden our database of experience, it also helps us see the different approaches or thought processes we each use. By taking time to explore WHY we think differently, what led us to think of, or perhaps not think of, a particular diagnosis, we get some insight in to what has shaped our thinking. Is it a case we have seen previously, a piece of information picked up at a conference or in a journal, or is it a personal experience of illness in family or friends? Practicing our thinking with others helps us learn from each other’s ideas, grow our database of experience and improve our reasoning.

Finally, one can also create simulated cases and discuss our reasoning around these with colleagues. The obvious time for this is in the simulation laboratory or after some in situ sim but there are lower tech ways of doing this. Consider using ‘The Random Patient Generator’ that I have written about previously. Exploring our diagnostic thinking with a group of clinicians can give us a great deal of insight in to how differently we all view cases and how we respond to certain cues in cases. We can then take that experience to the shop floor and use it to help trainees develop their thinking as I have written about in another blog post.

Feedback, Recording our Thoughts and Practice, three ways I believe we can improve our diagnostic analogical reasoning in resuscitation.

So, what was wrong with our patient who arrived in Resus about 15 minutes ago? Perhaps she is eclamptic, maybe she has an intracranial haemorrhage or is it even possible that she has been poisoned by her ‘loving’ husband, I don’t know… BUT I do know this, whatever is wrong, the best chance for her and her baby’s survival is that she is treated by a clinician who has embraced analogical thinking, a clinician who understands the importance of feedback, one who records what they are thinking and who has deliberately practiced how they think in advance. An expert thinker, ready for just such a situation.

Simon

Great talk, great blogpost!

Thanks! And Enjoy Amsterdam the rest of your stay.

Greetings Timo

LikeLike

Great blog Simon. Kind of glad I don’t find myself in resus too often these days… my thinking isn’t what it used to be!

LikeLike

Loved your presentation and workshop at ResusNL. How nice to re-read your talk with this blogpost! Keep up the good work!!!

Greetz from the Netherlands

Femke

LikeLike